MAKING AN EVALUATION

Corn Planting

Performance

By Greg Stewart, OMAFRA

Corn Specialist

Taking a close

look at your corn fields this spring for yield-limiting conditions

will help with future equipment and management decisions.

When assessing your corn planters (operator and machine) performance this year,

there are three specific things that you should look for: uniformity of plant

spacing, uniformity of plant emergence, and consistency in obtaining desired

final plant populations. Most of us appreciate the perfect picket fence field

of corn, but it's important to understand which elements of your corn plant

stand contribute the most to your cropping profitability.

Uniformity of

Spacing

Corn plants that are perfectly spaced down the row would seem to have a much

better chance to optimize final yields. Equipment companies and agronomy researchers

have contributed to producing more uniformly spaced corn fields and to promoting

their necessity. Spacing uniformity can be measured by the occurrence of doubles

or skips, or in terms of standard deviation. An absolutely perfect stand where

every plant is exactly 7.25 inches, (28,840 plants per acre in 30-inch rows)

from its neighbour would have a standard deviation of zero. If plants on average

varied plus or minus two inches from the desired 7.25 inches then the standard

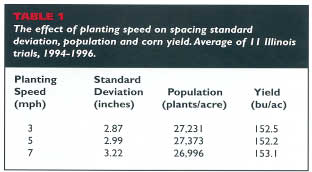

deviation would be two. Dr. Bob Nielsen (Purdue University, Indiana) has conducted

extensive investigations into the effects of plant spacing variability on final

yield. He calculates that every additional one inch of standard deviation decreases

yields by 2.5 bu/ac. When former University of Guelph professor Tony Vyn and

I started narrow-row corn research in 1995, we went at it with the idea that

plant-spacing uniformity might be less of an issue in 20-inch row corn due to

the increasing ability for neighbouring rows to compensate for gaps. This research

consisted of several different row widths, while imposing spacing uniformity

differences by hand thinning shortly after emergence. Interestingly, this research

has not shown any yield loss due to increased plant-spacing variability, regardless

of row widths.

I

have been concerned that the thinning operation might have been skewing the

results by disturbing the neighbouring soil. So in 1999, we applied Roundup

herbicide (via bingo daubers) to the plants that needed to be removed from the

overplanted rows. The results were the same as in previous years: relatively

poor plant-spacing uniformity yielded the same as the most precisely spaced

plots. Earlier research at the University of Guelph by Vyn and Terry Daynard

also indicated that differences in plant-spacing uniformity had little effect

on final yields. Discrepancies between different research findings may have

something to do with hybrids, plant populations, or other factors that confound

spacing effects.

I

have been concerned that the thinning operation might have been skewing the

results by disturbing the neighbouring soil. So in 1999, we applied Roundup

herbicide (via bingo daubers) to the plants that needed to be removed from the

overplanted rows. The results were the same as in previous years: relatively

poor plant-spacing uniformity yielded the same as the most precisely spaced

plots. Earlier research at the University of Guelph by Vyn and Terry Daynard

also indicated that differences in plant-spacing uniformity had little effect

on final yields. Discrepancies between different research findings may have

something to do with hybrids, plant populations, or other factors that confound

spacing effects.

The point behind this discussion is not to encourage poor planter set-up, or

ignore unevenly spaced corn, but to underline the following points:

Uniformity of Emergence

Perhaps one of the most significant changes that you might consider making

when evaluating corn planter performance is in looking at the uniformity of

the plant emergence. Because it's almost impossible to find time to actually

monitor corn  plants

as they emerge, you will need to examine corn plant leaf numbers to see if

the plants are all at the same stage of development. Some substantial research

both in Ontario and in the U.S. Corn Belt has indicated that when neighbouring

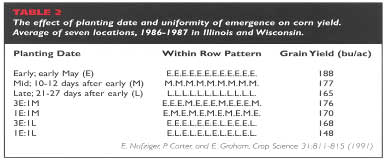

corn plants are not uniform in size yields will suffer. Dr. Emerson Nafziger

(University of Illinois) has reported corn yields based on plots which have

differences in uniformity of emergence (Table 2). These hand-planted plots

consisted of uniformly planted plots on three separate dates. They also included

various combinations of plots where certain fractions of the plants were planted

later to simulate delayed emergence. In Table 2 you notice the treatment labeled

3E:1M consisted of one plant in every four being planted 10 days later than

the neighbouring in-row plants. This resulted in a decrease in yield of 12

bushels (176 bu/ac) compared to the plots where all plants emerged uniformly

on the early planting date (188 bu/ac).

plants

as they emerge, you will need to examine corn plant leaf numbers to see if

the plants are all at the same stage of development. Some substantial research

both in Ontario and in the U.S. Corn Belt has indicated that when neighbouring

corn plants are not uniform in size yields will suffer. Dr. Emerson Nafziger

(University of Illinois) has reported corn yields based on plots which have

differences in uniformity of emergence (Table 2). These hand-planted plots

consisted of uniformly planted plots on three separate dates. They also included

various combinations of plots where certain fractions of the plants were planted

later to simulate delayed emergence. In Table 2 you notice the treatment labeled

3E:1M consisted of one plant in every four being planted 10 days later than

the neighbouring in-row plants. This resulted in a decrease in yield of 12

bushels (176 bu/ac) compared to the plots where all plants emerged uniformly

on the early planting date (188 bu/ac).

When you walk your corn fields, keep the following ideas in mind:

Plant Populations

The third element that should concern you is whether you actually have the

desired final plant stand. Measure off 17.5 feet of row (30-inch rows) and

count all the corn plants, multiply by 1,000 and you have the number of plants

per acre. In Ontario, final plant populations should probably be 26,000 -

32,000 plants per acre. If your planter is not falling somewhere in this range,

identify

this as one of the first improvements to be made. If your plant stands are

low, is it because you are not allowing for a 5-10 per cent reduction from

seed drop to final stands? A recent research report published in the Agronomy

Journal (D. Bullock et. al., 1998) indicated that the optimum final plant

population in the midwest Corn Belt on average is 27,160 plants per acre.

These researchers also predicted that for every 15 bu/ac increase in a field’s

yield potential (or parts of fields), economically optimal populations increased

by 450 plants per acre. So in Ontario, while we may generally shoot for slightly

higher average final stands than in the midwest, you will also want to ensure

that your productive fields are near the upper end of the plant population

range. Fields that are traditionally lower yielding because of low water-holding

capacity, poor soil structure, etc., have economic optimal populations lower

in the range.

identify

this as one of the first improvements to be made. If your plant stands are

low, is it because you are not allowing for a 5-10 per cent reduction from

seed drop to final stands? A recent research report published in the Agronomy

Journal (D. Bullock et. al., 1998) indicated that the optimum final plant

population in the midwest Corn Belt on average is 27,160 plants per acre.

These researchers also predicted that for every 15 bu/ac increase in a field’s

yield potential (or parts of fields), economically optimal populations increased

by 450 plants per acre. So in Ontario, while we may generally shoot for slightly

higher average final stands than in the midwest, you will also want to ensure

that your productive fields are near the upper end of the plant population

range. Fields that are traditionally lower yielding because of low water-holding

capacity, poor soil structure, etc., have economic optimal populations lower

in the range.

Keep in mind the following other points:

So, when you are out enjoying your twilight stroll through your corn field this June, don't forget to take along your clip board, pencil, calculator and yard stick!